Consuming REST services using the CPR

Introduction to REST and HTTP

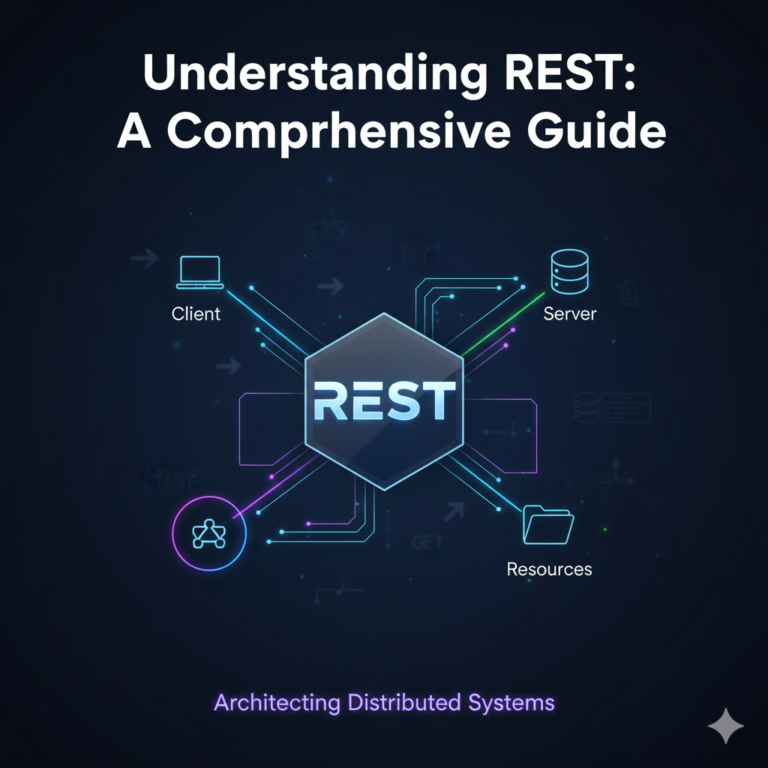

Understanding REST Architecture

Representational State Transfer (REST) is an architectural style for designing networked applications. It provides a set of principles for building scalable and loosely coupled systems. Understanding REST architecture is crucial for developing web services and consuming APIs effectively. Below is a detailed explanation of the key concepts of REST architecture:

1. Resources:

- Core Concept: In REST architecture, everything is considered a resource. A resource is an entity or object that can be accessed via a unique identifier (URI). Examples of resources include users, articles, products, etc.

- Identification: Each resource is identified by a Uniform Resource Identifier (URI). URIs provide a globally unique way to identify resources.

- Representation: Resources can have multiple representations, such as JSON, XML, HTML, or plaintext. Clients can request a specific representation of a resource based on their requirements.

2. Uniform Interface:

- Key Principle: REST emphasizes a uniform interface between components. This simplifies communication and promotes scalability and modifiability.

- Four Constraints: The uniform interface constraint in REST consists of four sub-constraints:

- Identification of Resources: Resources are identified by URIs.

- Manipulation of Resources through Representations: Clients manipulate resources through the exchange of representations.

- Self-descriptive Messages: Each message includes metadata (e.g., media type) that describes how to process the message.

- Hypermedia as the Engine of Application State (HATEOAS): Responses include hyperlinks that allow clients to navigate the application’s state.

3. Statelessness:

- Definition: RESTful systems are stateless, meaning each request from a client to the server must contain all the information necessary to understand and process the request.

- No Client Context: Servers do not store client state between requests. This improves scalability and reliability.

- State Transfer: Any state required by the server to fulfill a request must be transferred in the request itself, in parameters, headers, or the request body.

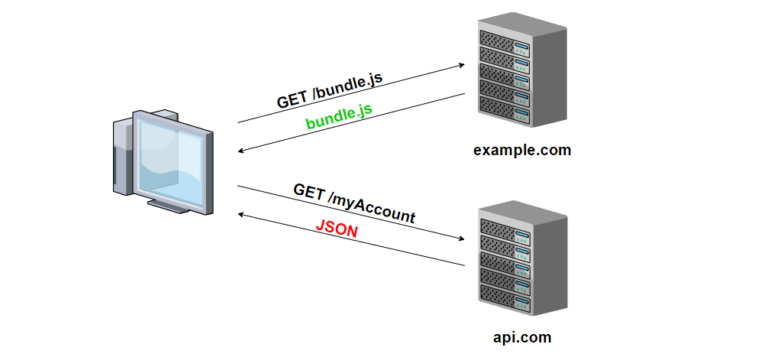

4. Client-Server Architecture:

- Separation of Concerns: REST architectures follow the client-server architectural style, where the client and server are independent entities that can evolve separately.

- Benefits: This separation enables better scalability, as the client and server can be optimized independently. It also enhances portability and simplicity.

5. Cacheability:

- Caching Support: REST encourages the use of caching to improve performance and scalability. Responses from the server should explicitly indicate whether they are cacheable or not.

- Client Caching: Clients can cache responses to future requests, reducing latency and server load.

- Server Caching: Servers can cache responses to reduce the computation and database load.

6. Layered System:

- Definition: REST allows for a layered system architecture, where intermediaries (e.g., proxies, gateways) can be used to improve scalability, security, and performance.

- Benefits: Layers can be added or removed without affecting the overall system, promoting flexibility and scalability.

7. Stateless Communication:

- Statelessness: RESTful communication between clients and servers is stateless, meaning each request is independent and contains all the information needed for processing.

- Benefits: Stateless communication simplifies server implementation and improves reliability and scalability.

Understanding REST architecture is essential for developing modern web applications and APIs. By following REST principles, developers can design scalable, maintainable, and interoperable systems that leverage the full potential of the web. Embracing REST architecture promotes simplicity, scalability, and flexibility in distributed systems.

Overview of HTTP methods (GET, POST, PUT, PATCH, DELETE)

HTTP (Hypertext Transfer Protocol) is a protocol used for communication between web servers and clients. It defines several methods (also known as verbs) that indicate the desired action to be performed on a resource. Each method has a specific purpose and usage. Below is an overview of the most commonly used HTTP methods:

1. GET

- Purpose: The GET method is used to request data from a specified resource.

- Usage: When a client sends a GET request, it retrieves information from the server without modifying it.

- Idempotent: GET requests are idempotent, meaning multiple identical requests will have the same effect as a single request.

- Example: Retrieving a user’s profile information from a web server.

2. POST

- Purpose: The POST method is used to submit data to be processed to a specified resource.

- Usage: When a client sends a POST request, it typically includes data in the request body, which the server then processes and potentially stores.

- Non-Idempotent: POST requests are non-idempotent, meaning multiple identical requests may have different effects.

- Example: Submitting a form on a web page to create a new user account.

3. PUT

- Purpose: The PUT method is used to update or replace a resource at a specified URI.

- Usage: When a client sends a PUT request, it replaces the target resource with the request payload.

- Idempotent: PUT requests are idempotent, meaning multiple identical requests will have the same effect as a single request.

- Example: Updating a user’s profile information with new data.

4. PATCH

- Purpose: The PATCH method is used to apply partial modifications to a resource.

- Usage: When a client sends a PATCH request, it applies modifications specified in the request payload to the target resource.

- Idempotent: PATCH requests may or may not be idempotent, depending on how the server handles them.

- Example: Updating only the email address field of a user’s profile.

5. DELETE

- Purpose: The DELETE method is used to delete a resource identified by a specified URI.

- Usage: When a client sends a DELETE request, it removes the target resource from the server.

- Idempotent: DELETE requests are idempotent, meaning multiple identical requests will have the same effect as a single request.

- Example: Deleting a user account from a database.

Additional Methods:

- OPTIONS: Used to describe the communication options for the target resource.

- HEAD: Similar to GET, but only retrieves the headers and not the actual content of the resource.

- TRACE: Used to echo the received request, mainly for diagnostic purposes.

- CONNECT: Used to establish a tunnel to the server identified by the target resource.

Understanding the various HTTP methods is essential for building robust and secure web applications. Each method has its specific purpose and usage, and knowing when to use them appropriately ensures efficient communication between clients and servers.

Introduction to HTTP status codes

HTTP (Hypertext Transfer Protocol) status codes are a crucial part of the HTTP protocol. They are three-digit numeric codes returned by a server in response to a client’s request to indicate the outcome of the request. Understanding HTTP status codes is essential for diagnosing and troubleshooting web server and application issues. Below is an overview of the most common HTTP status codes:

1. Informational (1xx):

- 100 Continue: The server has received the initial part of the request and will continue to process it.

- 101 Switching Protocols: The server is switching protocols as requested by the client (e.g., upgrading to WebSocket).

2. Success (2xx):

- 200 OK: The request was successful, and the server has returned the requested content.

- 201 Created: The request has been fulfilled, and a new resource has been created.

- 204 No Content: The server successfully processed the request, but there is no content to return.

3. Redirection (3xx):

- 301 Moved Permanently: The requested resource has been permanently moved to a new URL.

- 302 Found (Moved Temporarily): The requested resource has been temporarily moved to a different URL.

- 304 Not Modified: The resource has not been modified since the last request, and the server does not need to send the content again.

4. Client Error (4xx):

- 400 Bad Request: The server could not understand the request due to invalid syntax or other client-side errors.

- 401 Unauthorized: The request requires authentication, and the client needs to provide valid credentials.

- 403 Forbidden: The server understood the request but refuses to authorize it.

- 404 Not Found: The requested resource could not be found on the server.

5. Server Error (5xx):

- 500 Internal Server Error: A generic error message indicating that something has gone wrong on the server.

- 502 Bad Gateway: The server received an invalid response from an upstream server while trying to fulfill the request.

- 503 Service Unavailable: The server is temporarily unable to handle the request due to maintenance or overloading.

- 504 Gateway Timeout: The server did not receive a timely response from an upstream server while acting as a gateway or proxy.

Usage and Importance:

- Debugging: HTTP status codes provide valuable information for diagnosing issues during web development and troubleshooting.

- Error Handling: Web applications should handle different status codes gracefully to provide meaningful feedback to users.

- SEO (Search Engine Optimization): Properly handling status codes, especially 3xx and 4xx, can impact a website’s search engine rankings and user experience.

HTTP status codes play a critical role in web development by providing information about the outcome of HTTP requests. Understanding the meaning and usage of different status codes is essential for building reliable and user-friendly web applications.

Basics of HTTP Headers and Request/Response Structure

HTTP (Hypertext Transfer Protocol) headers are essential components of HTTP requests and responses. They provide additional information about the request or response and enable communication between clients and servers. Understanding HTTP headers and the structure of HTTP requests and responses is crucial for building and consuming web services effectively. Below is a detailed overview of the basics of HTTP headers and the request/response structure:

1. HTTP Headers:

- Definition: HTTP headers are key-value pairs included in both requests and responses. They provide metadata about the request or response, such as content type, encoding, caching directives, authentication credentials, etc.

- Types of Headers:

- General Headers: Apply to both requests and responses, such as

Date,Connection,Cache-Control. - Request Headers: Sent by the client to the server and provide additional information about the request, such as

User-Agent,Host,Accept. - Response Headers: Sent by the server to the client and provide additional information about the response, such as

Content-Type,Content-Length,Server. - Entity Headers: Apply to the body of the request or response, such as

Content-Type,Content-Length.

- General Headers: Apply to both requests and responses, such as

- Example:

plaintext GET /index.html HTTP/1.1 Host: www.example.com User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 10.0; Win64; x64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/96.0.4664.110 Safari/537.36 Accept: text/html,application/xhtml+xml,application/xml;q=0.9,image/avif,image/webp,image/apng,*/*;q=0.8,application/signed-exchange;v=b3;q=0.9

2. HTTP Request Structure:

- Components:

- Request Line: Specifies the HTTP method, target URL (URI), and HTTP version.

- Headers: Additional metadata about the request, such as content type, encoding, and authentication credentials.

- Optional Body: Some requests may include a message body, such as in POST or PUT requests.

- Example:

plaintext GET /index.html HTTP/1.1 Host: www.example.com User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 10.0; Win64; x64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/96.0.4664.110 Safari/537.36 Accept: text/html,application/xhtml+xml,application/xml;q=0.9,image/avif,image/webp,image/apng,*/*;q=0.8,application/signed-exchange;v=b3;q=0.9

3. HTTP Response Structure:

- Components:

- Status Line: Specifies the HTTP version, status code, and status message.

- Headers: Additional metadata about the response, such as content type, length, and caching directives.

- Optional Body: The response body containing the requested content, such as HTML, JSON, or binary data.

- Example:

HTTP/1.1 200 OK Date: Thu, 31 Mar 2024 12:00:00 GMT Content-Type: text/html Content-Length: 1274 <!DOCTYPE html> <html> <head> <title>Example Page</title> </head> <body> <h1>Welcome to Example Page</h1> <p>This is a sample HTML page.</p> </body> </html>

HTTP headers and the structure of HTTP requests and responses are fundamental concepts in web development. By understanding these concepts, developers can effectively communicate between clients and servers, control the behavior of requests and responses, and build robust and efficient web applications.

Introduction to CPR Library

Introduction to CPR Library with CMake Project

CPR (C++ Requests) is a modern C++ library for making HTTP requests. It is designed to be simple, efficient, and easy to use. This guide will provide an introduction to using the CPR library in a CMake project.

1. Installing CPR Library:

Before integrating CPR into your CMake project, you need to install the library. CPR can be installed using package managers or by building it from source.

- Using Package Managers: CPR is available on some package managers like Conan and vcpkg. You can use these package managers to install CPR and manage its dependencies.

- Building from Source: If you prefer to build CPR from source, you can clone the GitHub repository and build it manually. Follow the instructions provided in the CPR repository’s README file for building and installing.

2. Setting Up a CMake Project:

Assuming you have a CMake project set up, you need to configure your CMakeLists.txt file to include CPR and link it to your project.

- CMakeLists.txt Example:

cmake_minimum_required(VERSION 3.10) project(MyProject) # Find CPR package find_package(cpr CONFIG REQUIRED) # Add your executable and link CPR library add_executable(MyExecutable main.cpp) target_link_libraries(MyExecutable PRIVATE cpr::cpr)

3. Making HTTP Requests with CPR:

Once CPR is integrated into your CMake project, you can start making HTTP requests using its intuitive API.

- Example Usage:

#include <iostream> #include <cpr/cpr.h> int main() { // Make a GET request auto response = cpr::Get(cpr::Url{"https://api.example.com/data"}); // Check if request was successful if (response.status_code == 200) { std::cout << "Response: " << response.text << std::endl; } else { std::cerr << "Error: " << response.status_code << std::endl; } return 0; }

4. Handling Dependencies:

Ensure that your project’s dependencies, including CPR, are properly managed. If you’re using package managers like Conan or vcpkg, make sure they are properly configured in your CMake project.

5. Building and Running:

Once everything is set up, build your CMake project as usual. If there are no errors, you can run your executable, and it should make HTTP requests using CPR.

Conclusion:

Integrating CPR into a CMake project is straightforward and provides a convenient way to make HTTP requests in C++. With CPR, you can easily communicate with RESTful APIs and web services within your C++ applications.

Note: Make sure to refer to the CPR documentation and the specific documentation for your package manager (if applicable) for detailed installation and usage instructions.

References:

- CPR GitHub Repository: https://github.com/whoshuu/cpr

- CMake Documentation: https://cmake.org/documentation/

- CPR Documentation: https://docs.libcpr.org/

Understanding the features and capabilities of CPR

Understanding the features and capabilities of CPR (C++ Requests) involves exploring its API and understanding how it facilitates making HTTP requests and handling responses efficiently. Below, I’ll outline some key features of CPR along with code samples to demonstrate their usage:

1. Simplified API for Making HTTP Requests:

CPR provides a simple and intuitive API for making various types of HTTP requests, such as GET, POST, PUT, DELETE, etc.

Code Sample – Making a GET Request:

#include <cpr/cpr.h>

int main() {

// Make a GET request

auto response = cpr::Get(cpr::Url{"https://api.example.com/data"});

// Check if request was successful

if (response.status_code == 200) {

// Handle successful response

// Print response body

std::cout << "Response: " << response.text << std::endl;

} else {

// Handle error response

std::cerr << "Error: " << response.status_code << std::endl;

}

return 0;

}2. Customization Options for Requests:

CPR allows customization of requests by providing options for setting headers, parameters, authentication, proxies, timeouts, SSL options, etc.

Code Sample – Making a POST Request with Custom Headers:

#include <cpr/cpr.h>

int main() {

// Define custom headers

cpr::Header headers{

{"Content-Type", "application/json"},

{"Authorization", "Bearer your_access_token"}

};

// Make a POST request with custom headers

auto response = cpr::Post(cpr::Url{"https://api.example.com/post"},

cpr::Header{{"Accept", "application/json"}},

cpr::Body{"{\"key\": \"value\"}"},

headers);

// Process response...

return 0;

}3. Handling Response Data:

CPR provides convenient ways to handle response data, including accessing response status code, headers, body content, and parsing JSON/XML responses.

Code Sample – Accessing Response Data:

#include <cpr/cpr.h>

int main() {

// Make a GET request

auto response = cpr::Get(cpr::Url{"https://api.example.com/data"});

// Accessing response data

int status_code = response.status_code;

std::string content_type = response.header["content-type"];

std::string body = response.text;

// Process response...

return 0;

}4. Asynchronous Requests:

CPR supports making asynchronous HTTP requests, allowing your application to perform other tasks while waiting for the response.

Code Sample – Making an Asynchronous Request:

#include <iostream>

#include <cpr/cpr.h>

int main() {

// Make an asynchronous GET request

auto async_response = cpr::GetAsync(cpr::Url{"https://api.example.com/data"});

// Do other tasks while waiting for the response...

// Wait for the response

auto response = async_response.get();

// Process response...

return 0;

}CPR provides a powerful and easy-to-use API for making HTTP requests and handling responses in C++ applications. By understanding its features and capabilities, you can effectively interact with RESTful APIs and web services within your C++ projects.

Experimenting with these code samples and exploring the CPR documentation and examples further will help you gain proficiency in using CPR for your HTTP communication needs.

Handling response data (JSON, XML, plaintext) in GET requests

Handling response data in various formats like JSON, XML, and plaintext when making GET requests with CPR involves parsing the response body according to the expected format. Below are code samples demonstrating how to handle response data in JSON, XML, and plaintext formats using CPR, along with the nlohmann JSON library for JSON parsing:

1. Handling JSON Response:

When the server responds with JSON data, you can parse the JSON string using a JSON parsing library like nlohmann JSON.

Code Sample – Handling JSON Response:

#include <iostream>

#include <cpr/cpr.h>

#include <nlohmann/json.hpp>

using json = nlohmann::json;

int main() {

// Make a GET request

auto response = cpr::Get(cpr::Url{"https://api.example.com/data"});

// Check if request was successful

if (response.status_code == 200) {

// Parse JSON response

json jsonResponse = json::parse(response.text);

// Access JSON data

std::string name = jsonResponse["name"];

int age = jsonResponse["age"];

// Print JSON data

std::cout << "Name: " << name << std::endl;

std::cout << "Age: " << age << std::endl;

} else {

std::cerr << "Error: " << response.status_code << std::endl;

}

return 0;

}2. Handling XML Response:

When the server responds with XML data, you can use XML parsing libraries like pugixml to parse the XML string and extract the required information.

Code Sample – Handling XML Response:

#include <iostream>

#include <cpr/cpr.h>

#include <pugixml.hpp>

int main() {

// Make a GET request

auto response = cpr::Get(cpr::Url{"https://api.example.com/data"});

// Check if request was successful

if (response.status_code == 200) {

// Parse XML response

pugi::xml_document doc;

if (doc.load_string(response.text.c_str())) {

// Access XML data

pugi::xml_node node = doc.child("root").child("element");

std::string value = node.child_value("tag");

// Print XML data

std::cout << "Value: " << value << std::endl;

} else {

std::cerr << "Error parsing XML response" << std::endl;

}

} else {

std::cerr << "Error: " << response.status_code << std::endl;

}

return 0;

}3. Handling Plaintext Response:

When the server responds with plaintext data, you can directly access the response body as a string and process it accordingly.

Code Sample – Handling Plaintext Response:

#include <iostream>

#include <cpr/cpr.h>

int main() {

// Make a GET request

auto response = cpr::Get(cpr::Url{"https://api.example.com/data"});

// Check if request was successful

if (response.status_code == 200) {

// Access plaintext response

std::string plaintext = response.text;

// Process plaintext data

std::cout << "Plaintext Response: " << plaintext << std::endl;

} else {

std::cerr << "Error: " << response.status_code << std::endl;

}

return 0;

}Handling response data in various formats like JSON, XML, and plaintext when making GET requests with CPR involves parsing the response body according to the expected format. By using appropriate parsing libraries like nlohmann JSON for JSON data and pugixml for XML data, you can effectively process the response data and extract the required information for your application.

Error handling in GET requests

Error handling in GET requests with CPR involves checking the status code of the response to determine if the request was successful or encountered an error. CPR provides status codes along with the response, allowing you to handle errors appropriately. Below is a code sample demonstrating error handling in GET requests using CPR:

#include <iostream>

#include <cpr/cpr.h>

int main() {

// Make a GET request

auto response = cpr::Get(cpr::Url{"https://api.example.com/data"});

// Check if request was successful

if (response.status_code == 200) {

// Handle successful response

std::cout << "Response: " << response.text << std::endl;

} else {

// Handle error response

std::cerr << "Error: " << response.status_code << std::endl;

// Print error details if available

if (!response.error.message.empty()) {

std::cerr << "Error Message: " << response.error.message << std::endl;

}

}

return 0;

}In this code sample:

- We make a GET request using

cpr::Get. - We check the

status_codefield of the response to determine if the request was successful (status code 200) or encountered an error. - If the status code indicates an error, we print the status code and, if available, the error message provided by CPR.

Additional Error Handling:

You can enhance error handling by considering additional factors such as timeouts, connection errors, and invalid responses. CPR provides error information through the error field of the response, which includes the error code, message, and any other relevant details.

Example with Timeout Handling:

#include <iostream>

#include <cpr/cpr.h>

int main() {

// Set timeout (in milliseconds)

cpr::Timeout timeout{5000}; // 5 seconds

// Make a GET request with timeout

auto response = cpr::Get(cpr::Url{"https://api.example.com/data"}, timeout);

// Check if request was successful

if (response.status_code == 200) {

// Handle successful response

std::cout << "Response: " << response.text << std::endl;

} else {

// Handle error response

std::cerr << "Error: " << response.status_code << std::endl;

// Print error details if available

if (!response.error.message.empty()) {

std::cerr << "Error Message: " << response.error.message << std::endl;

}

}

return 0;

}In this example, we set a timeout of 5 seconds for the GET request using cpr::Timeout. If the request exceeds the specified timeout, CPR will generate a timeout error, which can be handled similarly to other error responses.

Error handling in GET requests with CPR involves checking the status code and error details provided by the response. By appropriately handling errors, your application can gracefully recover from unexpected situations and provide meaningful feedback to users or log the errors for further investigation.

Making POST Requests

Understanding POST requests

POST requests are commonly used in web development to send data to a server to create or update a resource. Understanding how to make POST requests with CPR involves specifying the request URL, payload (data to be sent), and any additional options. Below, I’ll explain the basics of POST requests with CPR and provide a code sample:

Making a POST Request with CPR:

To make a POST request with CPR, you typically use the cpr::Post function, specifying the request URL, payload, headers (optional), and any other desired options.

Code Sample – Making a POST Request:

#include <iostream>

#include <cpr/cpr.h>

int main() {

// Define the request URL and payload (data to be sent)

cpr::Url url{"https://api.example.com/create"};

cpr::Payload payload{{"key", "value"}, {"another_key", "another_value"}};

// Make a POST request

auto response = cpr::Post(url, payload);

// Check if request was successful

if (response.status_code == 201) {

// Handle successful response

std::cout << "Resource created successfully!" << std::endl;

} else {

// Handle error response

std::cerr << "Error: " << response.status_code << std::endl;

}

return 0;

}In this code sample:

- We define the request URL (

url) and payload (payload) to be sent in the POST request. - We use the

cpr::Postfunction to make a POST request with the specified URL and payload. - We check the

status_codefield of the response to determine if the request was successful (status code 201 indicates resource created) or encountered an error.

Additional Options:

CPR provides additional options for customizing POST requests, such as setting custom headers, handling authentication, specifying timeouts, and more.

Code Sample – Making a POST Request with Custom Headers:

#include <iostream>

#include <cpr/cpr.h>

int main() {

// Define the request URL and payload

cpr::Url url{"https://api.example.com/create"};

cpr::Payload payload{{"key", "value"}, {"another_key", "another_value"}};

// Define custom headers

cpr::Header headers{{"Content-Type", "application/json"}, {"Authorization", "Bearer your_token"}};

// Make a POST request with custom headers

auto response = cpr::Post(url, payload, headers);

// Handle response...

return 0;

}Understanding how to make POST requests with CPR involves specifying the request URL, payload, and any additional options such as headers or authentication. By using the cpr::Post function, you can efficiently send data to a server to create or update resources as needed.

Experimenting with different options and handling responses appropriately will help you effectively integrate POST requests into your C++ applications using CPR.

Authentication and Security

Understanding authentication methods (Basic, OAuth, API keys)

Understanding authentication methods such as Basic Authentication, OAuth, and JWT (JSON Web Token) is crucial for securing web applications and APIs. Each method has its own approach to authenticating users and providing access to resources. Below, I’ll explain each authentication method briefly:

1. Basic Authentication:

Basic Authentication is a simple authentication scheme built into the HTTP protocol. It involves sending the user’s credentials (username and password) in the request headers, encoded using Base64 encoding. However, Basic Authentication is considered less secure as the credentials are sent in plaintext and can be easily intercepted. It’s often used in combination with HTTPS to encrypt the communication.

Example Header for Basic Authentication:

Authorization: Basic base64(username:password)2. OAuth (Open Authorization):

OAuth is an authorization framework that allows third-party services to access resources on behalf of the user without sharing their credentials. OAuth defines roles such as the resource owner (user), client (application), and authorization server. It uses access tokens to grant access to resources and refresh tokens to obtain new access tokens when they expire.

OAuth includes different grant types such as Authorization Code Grant, Implicit Grant, Client Credentials Grant, and Resource Owner Password Credentials Grant, each suited for different scenarios and security requirements.

3. JWT (JSON Web Token):

JWT is a compact, URL-safe means of representing claims to be transferred between two parties. It is commonly used for authentication and information exchange in web applications. JWTs consist of three parts: a header, a payload (claims), and a signature. They are digitally signed to ensure their integrity and can be encrypted for confidentiality.

JWTs are often used in combination with OAuth for access token representation. They can contain user information, permissions, and other relevant data. JWTs are self-contained and can be easily decoded by the server to verify their authenticity.

Conclusion:

Understanding authentication methods such as Basic Authentication, OAuth, and JWT is essential for building secure web applications and APIs. Each method has its own advantages, use cases, and security considerations. When implementing authentication in your application, it’s crucial to choose the appropriate method based on your requirements and consider factors such as security, usability, and scalability.

By familiarizing yourself with these authentication methods, you can design robust authentication mechanisms that protect user data and ensure secure access to resources.

Implementing JWT based Bearer authentication in CPR requests

Implementing JWT-based Bearer authentication in CPR requests involves adding the JWT token to the request headers. Typically, you’ll receive the JWT token after a successful authentication process, and you’ll include it in subsequent requests to authenticate the user. Below is a code sample demonstrating how to implement JWT-based Bearer authentication in CPR requests:

#include <iostream>

#include <cpr/cpr.h>

int main() {

// Define the request URL

cpr::Url url{"https://api.example.com/data"};

// Define the JWT token

std::string jwtToken = "your_jwt_token_here";

// Define the request headers with the JWT token

cpr::Header headers{{"Authorization", "Bearer " + jwtToken}};

// Make a GET request with JWT-based Bearer authentication

auto response = cpr::Get(url, headers);

// Check if request was successful

if (response.status_code == 200) {

// Handle successful response

std::cout << "Response: " << response.text << std::endl;

} else {

// Handle error response

std::cerr << "Error: " << response.status_code << std::endl;

}

return 0;

}In this code sample:

- We define the request URL (

url). - We define the JWT token (

jwtToken). This token should be obtained through a successful authentication process, such as logging in. - We define the request headers (

headers) with the JWT token included in theAuthorizationheader using the “Bearer” scheme. - We make a GET request to the specified URL with JWT-based Bearer authentication by passing the URL and headers to the

cpr::Getfunction.

Ensure that you replace "your_jwt_token_here" with the actual JWT token obtained during the authentication process.

This code demonstrates how to include JWT-based Bearer authentication in CPR requests, allowing you to securely authenticate users and access protected resources in your application.

Advanced Topics

Handling asynchronous requests with CPR

Handling asynchronous requests with CPR involves using the asynchronous functions provided by the library, such as cpr::GetAsync, cpr::PostAsync, etc. These functions return std::future objects representing the asynchronous operation, allowing you to retrieve the response asynchronously. Below is a code sample demonstrating how to handle asynchronous requests with CPR:

#include <iostream>

#include <future>

#include <cpr/cpr.h>

int main() {

// Define the request URL

cpr::Url url{"https://api.example.com/data"};

// Make an asynchronous GET request

auto async_response = cpr::GetAsync(url);

// Do other tasks while waiting for the response...

// Wait for the response asynchronously

auto future = async_response.get_future();

auto response = future.get();

// Check if request was successful

if (response.status_code == 200) {

// Handle successful response

std::cout << "Response: " << response.text << std::endl;

} else {

// Handle error response

std::cerr << "Error: " << response.status_code << std::endl;

}

return 0;

}In this code sample:

- We define the request URL (

url). - We make an asynchronous GET request using

cpr::GetAsync. - We perform other tasks while waiting for the response.

- We retrieve the response asynchronously using a

std::futureobject obtained from the asynchronous operation. - We check the response status code and handle the response accordingly.

This code demonstrates how to make asynchronous requests with CPR, allowing your application to perform other tasks while waiting for the response.

Working with custom HTTP headers

Working with custom HTTP headers in CPR involves adding custom headers to the request using the cpr::Header type. Custom headers are often used to provide additional information or configuration to the server. Below is a code sample demonstrating how to work with custom HTTP headers in CPR:

#include <iostream>

#include <cpr/cpr.h>

int main() {

// Define the request URL

cpr::Url url{"https://api.example.com/data"};

// Define custom headers

cpr::Header headers{

{"Custom-Header1", "Value1"},

{"Custom-Header2", "Value2"}

};

// Make a GET request with custom headers

auto response = cpr::Get(url, headers);

// Check if request was successful

if (response.status_code == 200) {

// Handle successful response

std::cout << "Response: " << response.text << std::endl;

} else {

// Handle error response

std::cerr << "Error: " << response.status_code << std::endl;

}

return 0;

}In this code sample:

- We define the request URL (

url). - We define custom headers (

headers) using an initializer list of pairs, where each pair represents a header key-value pair. - We make a GET request to the specified URL with the custom headers included in the request.

- We check the response status code and handle the response accordingly.

You can add any number of custom headers to the cpr::Header object as needed for your application. These custom headers can be used to pass authentication tokens, specify content types, provide metadata, or fulfill any other requirements of the server.

Handling redirects and timeouts

Handling redirects and timeouts in CPR involves setting appropriate options when making requests. CPR provides options to control behavior related to redirects and timeouts, allowing you to customize the behavior according to your application’s requirements. Below, I’ll explain how to handle redirects and timeouts in CPR:

Handling Redirects:

By default, CPR follows redirects automatically. You can control the maximum number of redirects to follow using the cpr::Redirect option.

Code Sample – Handling Redirects:

#include <iostream>

#include <cpr/cpr.h>

int main() {

// Define the request URL

cpr::Url url{"https://example.com/redirect"};

// Set maximum number of redirects to follow (default is 10)

cpr::Redirect redirectOption{3}; // Follow up to 3 redirects

// Make a GET request with redirect option

auto response = cpr::Get(url, redirectOption);

// Check if request was successful

if (response.status_code == 200) {

// Handle successful response

std::cout << "Response: " << response.text << std::endl;

} else {

// Handle error response

std::cerr << "Error: " << response.status_code << std::endl;

}

return 0;

}In this code sample:

- We define the request URL (

url). - We set the maximum number of redirects to follow to 3 using the

cpr::Redirectoption. - We make a GET request to the specified URL with the redirect option included.

Handling Timeouts:

Timeouts allow you to specify the maximum time to wait for a response from the server. You can set both connection and read timeouts using the cpr::Timeout option.

Code Sample – Handling Timeouts:

#include <iostream>

#include <cpr/cpr.h>

int main() {

// Define the request URL

cpr::Url url{"https://example.com/data"};

// Set connection and read timeouts (in milliseconds)

cpr::Timeout timeout{5000}; // 5 seconds

// Make a GET request with timeout option

auto response = cpr::Get(url, timeout);

// Check if request was successful

if (response.status_code == 200) {

// Handle successful response

std::cout << "Response: " << response.text << std::endl;

} else {

// Handle error response

std::cerr << "Error: " << response.status_code << std::endl;

}

return 0;

}In this code sample:

- We define the request URL (

url). - We set the connection and read timeouts to 5 seconds using the

cpr::Timeoutoption. - We make a GET request to the specified URL with the timeout option included.

Handling redirects and timeouts in CPR involves setting appropriate options when making requests. By customizing these options, you can control the behavior of CPR according to your application’s requirements, ensuring reliable communication with the server.

Ensure that you handle errors and exceptions appropriately when working with redirects and timeouts to ensure robustness and reliability in your application.